Trying something new: feijoada, a black bean stew with pork and beef. It’s smells ridiculously good.

To the Trinity and beyond!

I'm still plowing through articles and sources for a paper on St. Augustine's De Trinitate, but I think I've got the basic outline in my head. I had originally glommed on to his analogies (which occupy much of the book's second half), but things get technical very quickly in the secondary sources.

So I've broadened my scope and will (briefly) survey the before-and-after of Trinitarian thought, including the so-called East/West split. I want to answer the question: why does getting the Trinity right matter? Marie LaCugna's assertion that Trinitarian theology's speculative turn in the West has made it largely irrelevant to most Christians has some merit, even if I'm not entirely sure about the rest of her arguments. I've read the Augustine chapter from Thomas Joseph White's recently published The Trinity: On the Nature and Mystery of the One God and went ahead and ordered the book; it should arrive today.

For completeness, I've also been reading Edmund Hill, Lewis Ayres, Michel Barnes, John Cavadini, William Harmless, Earl Muller, and a host of others. I'm on the fence about trying to include Karl Rahner, but I'm not sure I can - or even should - avoid it. On the other hand, I think I've got a pretty good sample of pre-Nicene thought (the theophanies - Immanent moments - of Novatian, Justin Martyr, and Origen), so I probably owe space to the latter period as well.

So this weekend is some additional digging and hopefully tightening up the bibliography. In the background is another course on the Epistles, for which I owe an essay and additional reading in preparation for our next in-person class.

Currently reading: The Trinity (Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century) by Saint Augustine 📚

Pivoting between two piles of reading this evening: Origen on martyrdom to one side; articles/sources for a paper on Augustine’s De Trinitate to the other. So anyway, where’s the nearest desert?

Today was a strong-cocktail-before-dinner sort of day. This is a Boulevardier, which is basically a Negroni with bourbon. Dinner is a cassoulet of Italian sausage, gnocchi, and copious amounts of the garlic we harvested.

Tonight’s food pic is an Asian-style mushroom omelet, also from Milk Street. There’s supposed to be some green in there but we’re out of scallions and cilantro. :/

I should probably credit the website - both of these were generated by Stable Diffusion.

One more bit of AI-artwork in honor of St. Meinrad Archabbey. I also thought these turned out beautiful.

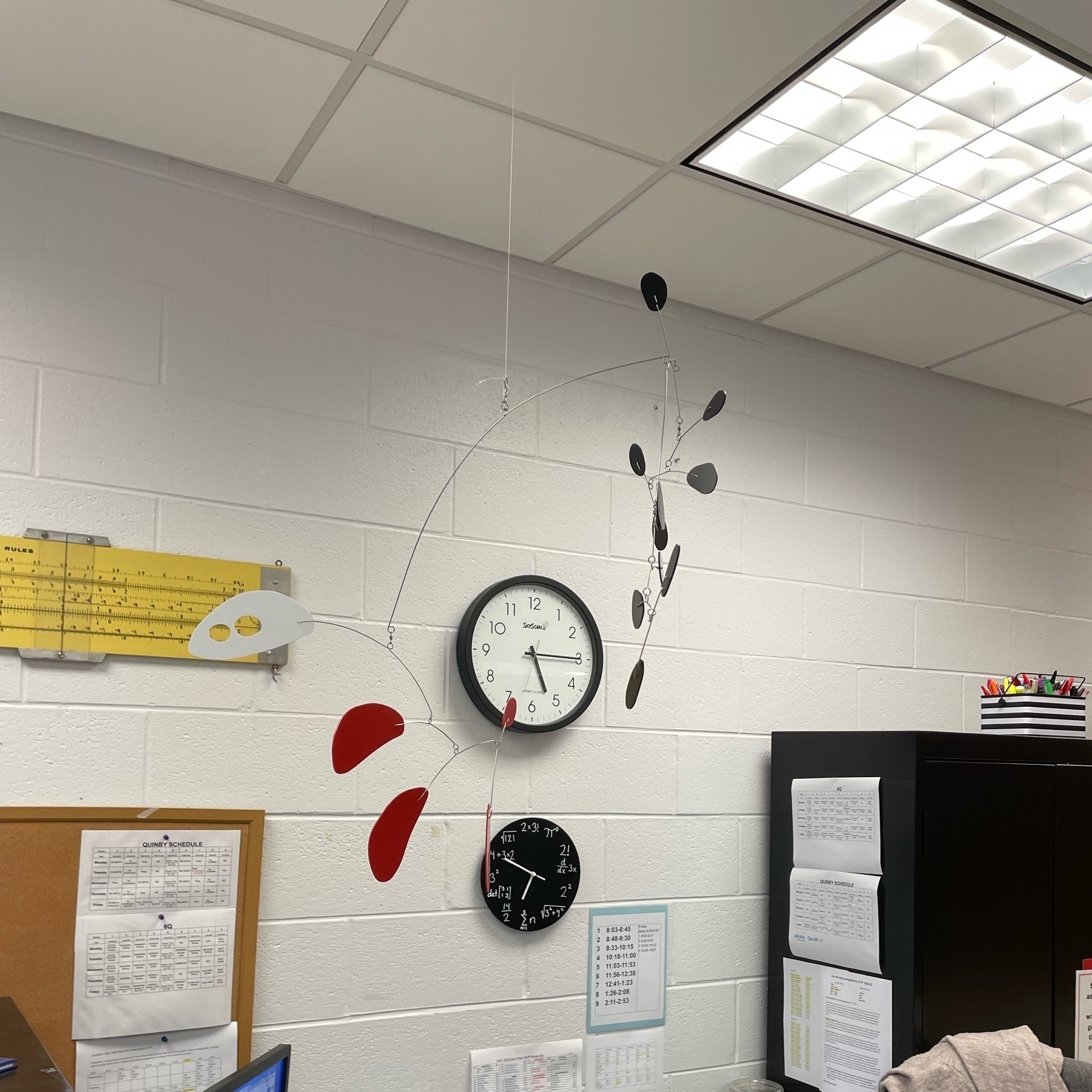

How much fun is a mobile in a math classroom? Too much! Too much fun! Beautiful artwork from #AtomicMobiles

Having some fun in the kitchen as I’ve recently taken on main dinner duties. This is harira, a Moroccan beef and chickpea stew. The recipe was in the recent issue of Milk Street.

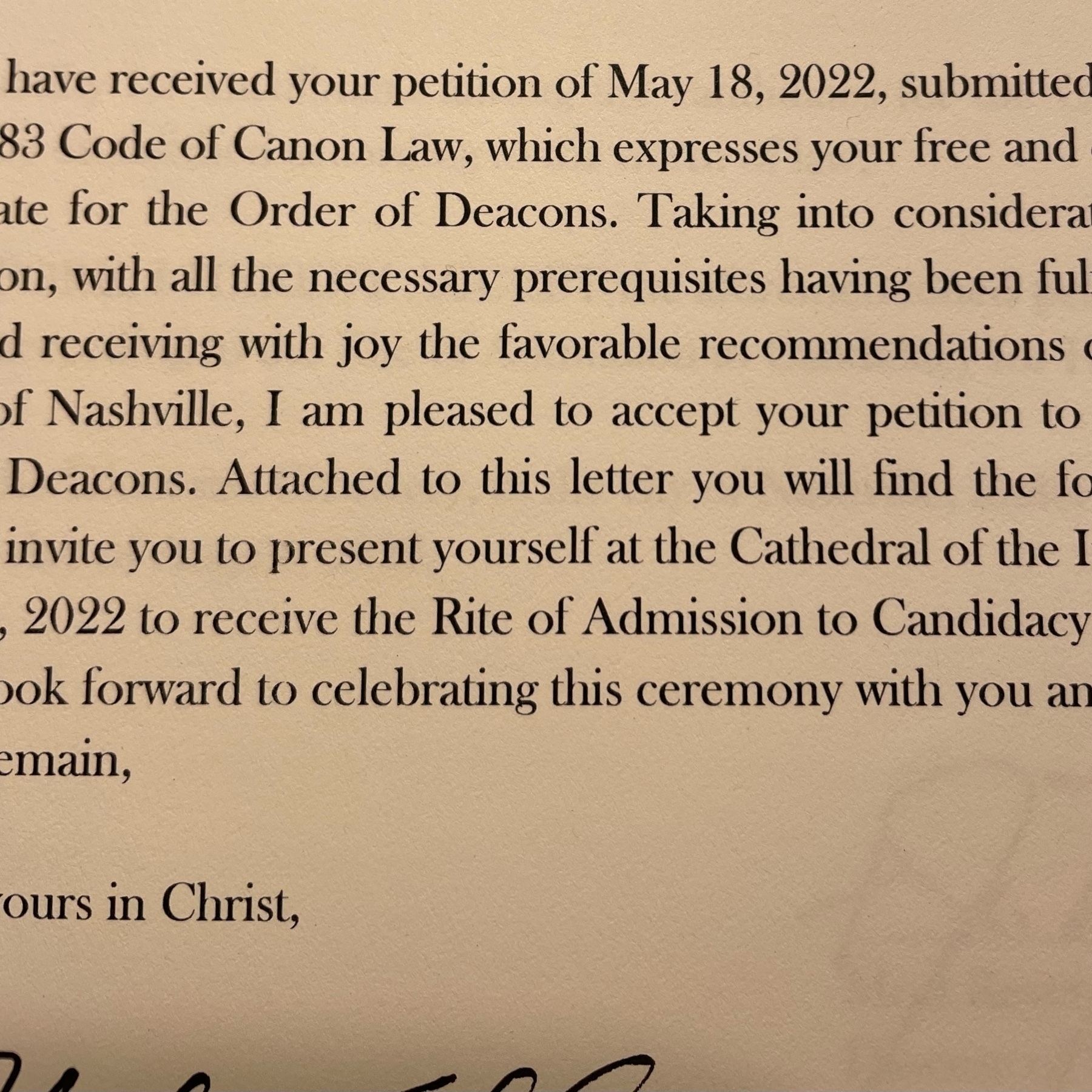

What a bunch we are! Beautiful Mass and an important step along this path. Can’t do it without the support of our families.

Breaking retreat silence to ask for your prayers - for me and all of the other men here with me likewise preparing for the Rite of Candidacy tomorrow!

Currently reading: Citizenship Papers by Wendell Berry 📚

Currently reading: Understanding the Diaconate: Historical, Theological, and Sociological Foundations by W. Shawn McKnight 📚

Enjoying a short summer break in classes before things pick up again in late August. There'll be a retreat that ends with our candidacy Mass, then we're back in the thick of it the weekend after. The shift from aspirant to candidate signals an end to the period of discernment even as we begin more intense study and practicums.

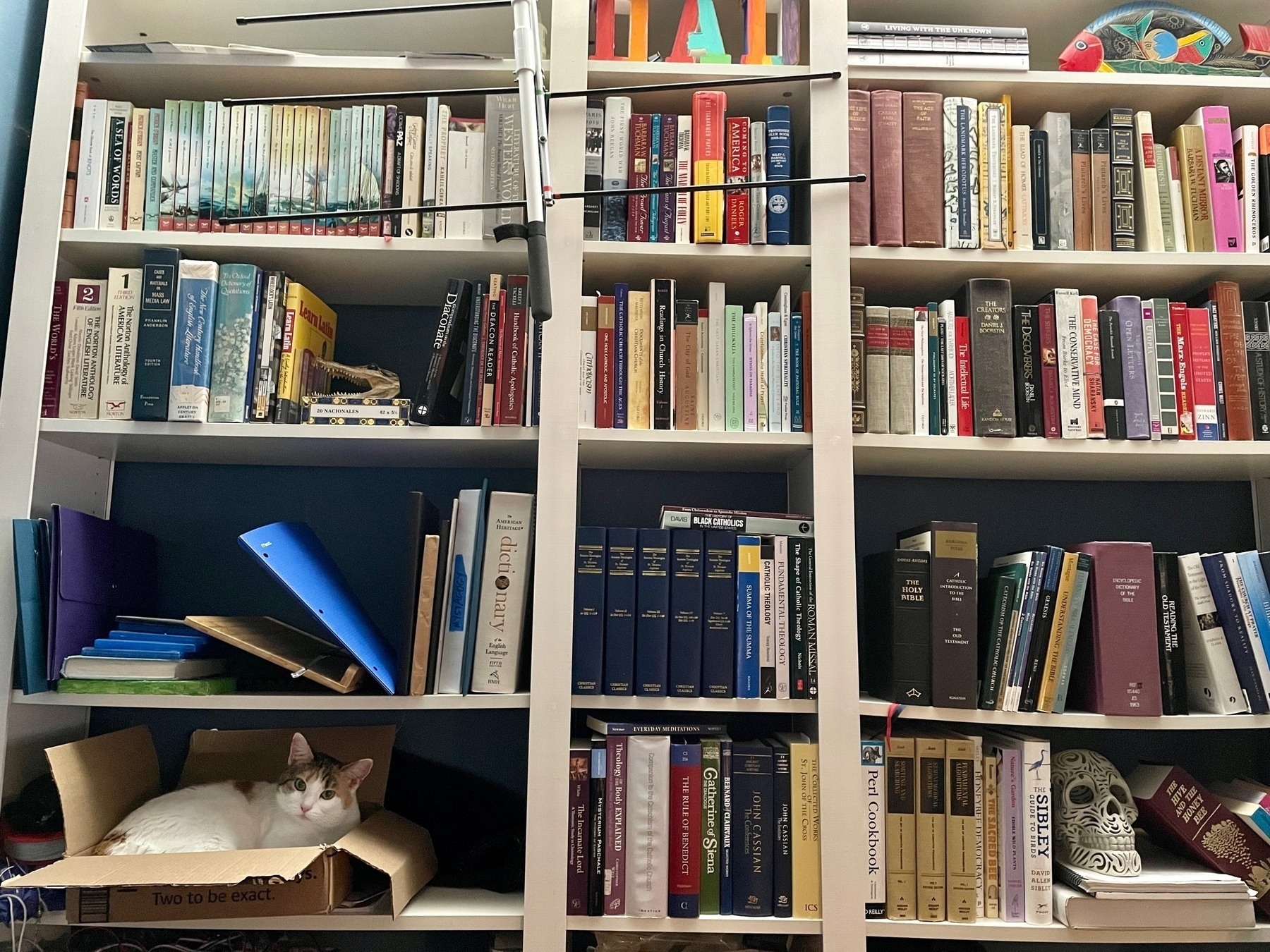

Accordingly, the booklists have landed, and here's what's on tap. First up is Early Church History, which I'll be doing online through most of the Fall:

- The Confessions, St. Augustine

- Early Christian Writings

- The Early Church, Chadwick

- On The Incarnation, St. Athanasius

- The Life of Antony and Letter to Marcellinus, St. Athanasius

-

Origen's basic writings

The in-person semester starts with Ministry of Deacon:

- The Deacon at Mass, Ditewig

- Theology of the Diaconate, Cummings, et al

-

The Deacon Reader, Keating

Neither of these lists includes the raft of articles and PDFs that have also been posted. For myself, I'm forcing myself into some downtime: catching up on some magazines, occasional video games (these days that means Vampire Survivors and Factorio), and I may even dust off the radio kit.

Mystagogy has wrapped up, so I'm going to pivot our neophytes into an 8-week bible study, portions of which we used when I was in class a couple of weeks ago. We tried to launch some small groups a few years ago, but Covid put an end to them about 2 weeks in. We've been trying to emphasize intentional discipleship these last few months. My prayer is that this group lectio will help us all to draw closer to Jesus, which is the essential prerequisite for...well, for basically everything else we do.

Currently reading: Ven Espíritu Creador: Meditaciones sobre el Veni Creator Prólogo de José Cardenal Ratzinger (Mística y Místicos) (Spanish Edition) by Raniero Cantalamesa 📚

Currently reading: The History of Black Catholics in the United States by Cyprian Davis 📚